Getting Started With GeoPandas

This notebook serves as a starter guide or template for doing geographical analysis using the GeoPandas library.

The dataset we will be using in this tutorial is from Analyze Boston. Analyze Boston is the City of Boston’s data hub and is a great resource for data sets regarding the city.

We will be working with two datasets. First is the 2020 CENSUS TRACTS IN BOSTON dataset, and second is the WICKED FREE WIFI LOCATIONS dataset. The first dataset contains the geographical boundaries of each census tract in Boston, and the second dataset contains the geographical location of each free wifi location in Boston.

# Start by importing the necessary packages

import pandas as pd

import geopandas as gpd

from shapely.geometry import Point, Polygon

# for visualizations :

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

When working with geographical data, .shp files are the most common format, however these files are often accompanied by other files with the same name but different extensions. For example, a .shp file might come with a .dbf, .prj, .shx, and .cpg file. These are necessary files and are used in the background. GeoPandas (and other GIS software) typically expect these files to be in the same directory as the .shp file and to share the same base filename.

# read in the census data

census = gpd.read_file('census/Census2020_BlockGroups.shp')

census.head()

| OBJECTID | STATEFP20 | COUNTYFP20 | TRACTCE20 | BLKGRPCE20 | GEOID20 | NAMELSAD20 | MTFCC20 | FUNCSTAT20 | ALAND20 | AWATER20 | INTPTLAT20 | INTPTLON20 | Shape_STAr | Shape_STLe | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 25 | 025 | 040600 | 1 | 250250406001 | Block Group 1 | G5030 | S | 1265377.0 | 413598.0 | +42.3833695 | -071.0707743 | 1.807118e+07 | 29256.866068 | POLYGON ((769378.692 2964626.314, 769385.078 2... |

| 1 | 2 | 25 | 025 | 051101 | 1 | 250250511011 | Block Group 1 | G5030 | S | 220626.0 | 0.0 | +42.3882285 | -071.0046816 | 2.374654e+06 | 9142.174252 | POLYGON ((788317.786 2966115.262, 788838.563 2... |

| 2 | 3 | 25 | 025 | 051101 | 4 | 250250511014 | Block Group 4 | G5030 | S | 227071.0 | 270.0 | +42.3913407 | -071.0020343 | 2.446949e+06 | 11579.546171 | POLYGON ((789538.125 2967889.427, 789539.214 2... |

| 3 | 4 | 25 | 025 | 981600 | 1 | 250259816001 | Block Group 1 | G5030 | S | 586981.0 | 158777.0 | +42.3886205 | -070.9934424 | 8.026752e+06 | 16626.718823 | POLYGON ((790938.417 2966482.118, 790974.619 2... |

| 4 | 5 | 25 | 025 | 010204 | 3 | 250250102043 | Block Group 3 | G5030 | S | 145888.0 | 0.0 | +42.3459611 | -071.1020344 | 1.570220e+06 | 5510.560013 | POLYGON ((762928.668 2951612.031, 763063.607 2... |

What makes a .shp file unique is the “geometry” column. The geometry column typically contains the coordinates or geometric properties of the features represented in the shapefile, such as points, lines, or polygons. For us, each row in our shapefile represents one census block group, and the geometry column stores a vectorized polygon boundaries of each block group that lets us see a visual representation of the block group.

census['geometry'][0]

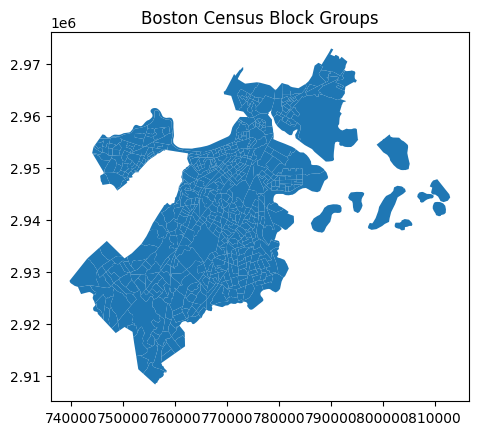

We can plot all of these block groups together to get a visual representation of the city of Boston.

census.plot()

plt.title('Boston Census Block Groups')

plt.show()

Now let’s read in our Wicked Free Wifi Locations shapefile

# read in the wifi locations shapefile

wfw = gpd.read_file('wifi/Wicked_Free_WiFi_Locations.shp')

wfw

| neighborho | neighbor_1 | device_ser | device_con | device_add | device_lat | device_lon | device_tag | etl_update | is_current | org1 | org2 | inside_out | landmark | ObjectId | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | N_568579452955534204 | Dorchester | Q2CK-H48M-P2E9 | DOT-BFD21-AP3 | 641 Columbia Rd., Dorchester, MA | 42.318336 | -71.063236 | BFD Engine-21 Outside | 2023-06-12 | 1 | BFD | NaN | Outside | Engine 21 | 1 | POINT (-7910723.209 5208784.596) |

| 1 | N_568579452955537848 | South Boston | Q2CK-LEG8-FAFN | SB-HIGHSCHOOL-AP2 | 95 G St., South Boston, MA | 42.332869 | -71.044891 | recently-added | 2023-06-12 | 1 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2 | POINT (-7908681.044 5210972.710) |

| 2 | N_568579452955538316 | Hyde Park | Q2CK-NERF-4JX7 | HP-BPDE18-AP2 | 1249 Hyde Park Ave., Hyde Park, MA | 42.256473 | -71.124219 | recently-added | 2023-06-12 | 1 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 3 | POINT (-7917511.803 5199475.676) |

| 3 | N_579275502070532581 | Roxbury | Q2CK-DSFT-7HTL | ROX-TROTTER-AP3 | Humbolt & Waumbeck St., Roxbury, MA | 42.313249 | -71.089180 | BPS Outside Trotter-School | 2023-06-12 | 1 | BPS | NaN | Outside | Trotter School | 4 | POINT (-7913611.287 5208018.690) |

| 4 | N_579275502070532581 | Roxbury | Q2CK-2D9P-VKGR | ROX-BFDE42-AP1 | 1870 Columbus Ave., Roxbury, MA | 42.318412 | -71.097758 | BFD Engine-42 Outside | 2023-06-12 | 1 | BFD | NaN | Outside | Engine 42 | 5 | POINT (-7914566.172 5208795.947) |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 255 | N_568579452955534204 | Dorchester | Q2CK-G9M2-VTK4 | DOT-BFD21-AP2 | 641 Columbia Rd., Dorchester, MA | 42.318336 | -71.063236 | BFD Engine-21 Outside | 2023-06-12 | 1 | BFD | NaN | Outside | Engine 21 | 256 | POINT (-7910723.209 5208784.596) |

| 256 | N_568579452955527921 | Parks | Q2CK-MP93-YDN3 | PARKS-COMMONEAST-AP1 | 139 Tremont St, Boston, MA 02111 | 42.355436 | -71.063827 | Boston-Common | 2023-06-12 | 1 | NaN | NaN | NaN | Boston Common | 257 | POINT (-7910789.066 5214371.556) |

| 257 | L_601230550253962688 | Navy Yard | Q2EK-HAXQ-8XW4 | NavyYard-AP2 | Navy yard Cambridge | 42.373720 | -71.053272 | NaN | 2023-06-12 | 1 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 258 | POINT (-7909614.112 5217126.360) |

| 258 | N_568579452955534204 | Dorchester | Q2CK-NJQU-RB55 | DOT-MATHER-AP3 | 24 Parrish St, Dorchester | 42.308397 | -71.061017 | recently-added | 2023-06-12 | 1 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 259 | POINT (-7910476.256 5207288.280) |

| 259 | N_579275502070532581 | Roxbury | Q2CK-NEZE-VRYJ | ROX-VINE-AP3 | 339 Dudley St, Roxbury | 42.326811 | -71.076707 | recently-added | 2023-06-12 | 1 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 260 | POINT (-7912222.881 5210060.516) |

260 rows × 16 columns

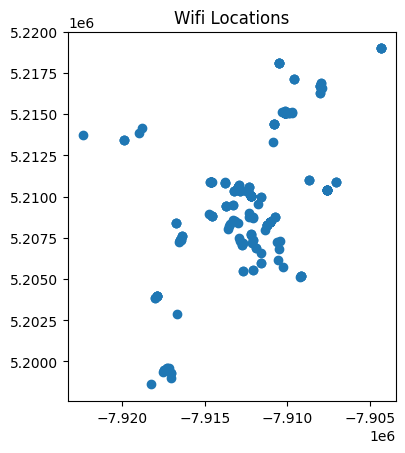

This time, our geometry column are single POINTs rather than whole POLYGONs, which makes sense because each row represents a single wifi location. After plotting them all together we see just a bunch of dots, which is not very helpful. We can make this plot more useful by adding the census block groups to the plot as well.

wfw.plot()

plt.title('Wifi Locations')

plt.show()

Data Cleaning

print(census.shape)

print(wfw.shape)

(581, 16)

(260, 16)

census.info()

<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 581 entries, 0 to 580

Data columns (total 16 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 OBJECTID 581 non-null int64

1 STATEFP20 581 non-null object

2 COUNTYFP20 581 non-null object

3 TRACTCE20 581 non-null object

4 BLKGRPCE20 581 non-null object

5 GEOID20 581 non-null object

6 NAMELSAD20 581 non-null object

7 MTFCC20 581 non-null object

8 FUNCSTAT20 581 non-null object

9 ALAND20 581 non-null float64

10 AWATER20 581 non-null float64

11 INTPTLAT20 581 non-null object

12 INTPTLON20 581 non-null object

13 Shape_STAr 581 non-null float64

14 Shape_STLe 581 non-null float64

15 geometry 581 non-null geometry

dtypes: float64(4), geometry(1), int64(1), object(10)

memory usage: 72.8+ KB

wfw.info()

<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 260 entries, 0 to 259

Data columns (total 16 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 neighborho 260 non-null object

1 neighbor_1 260 non-null object

2 device_ser 260 non-null object

3 device_con 250 non-null object

4 device_add 245 non-null object

5 device_lat 248 non-null float64

6 device_lon 248 non-null float64

7 device_tag 215 non-null object

8 etl_update 260 non-null object

9 is_current 260 non-null int64

10 org1 119 non-null object

11 org2 5 non-null object

12 inside_out 162 non-null object

13 landmark 168 non-null object

14 ObjectId 260 non-null int64

15 geometry 248 non-null geometry

dtypes: float64(2), geometry(1), int64(2), object(11)

memory usage: 32.6+ KB

Doesn’t look like there’s much to clean in the census data, but in the wifi dataset let’s just drop the organization columns because they contain the most nulls, and we don’t need them for our analysis.

wfw.drop(['org1', 'org2'], axis=1, inplace=True)

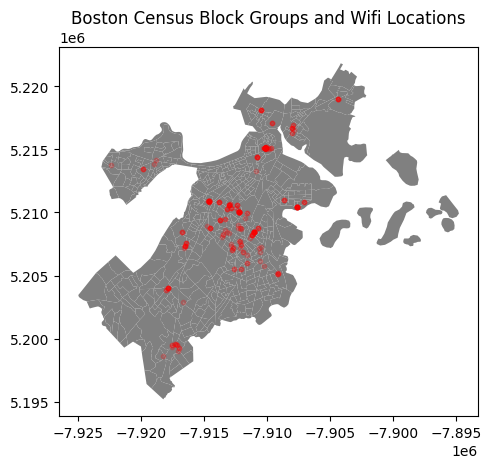

Showing the wifi locations on our census block group map

So we can see a map of Boston and a map of dots representing wifi locations separately, but how do I overlay these dots on top of the map of Boston to actuall see where in Boston these wifi locations are? First, check that the Coordinate Reference Systems (CRS) of both geodataframes are the same. The CRS specifies the coordinate system and reference frame used to define the spatial positions of the features represented in the file, and in order to overlay two geodataframes, they must have the same CRS.

# Check the CRS of both GeoDataFrames

print("Census CRS: ", census.crs)

print("Wifi CRS: ", wfw.crs)

Census CRS: PROJCS["NAD83 / Massachusetts Mainland (ftUS)",GEOGCS["NAD83",DATUM["North_American_Datum_1983",SPHEROID["GRS 1980",6378137,298.257222101,AUTHORITY["EPSG","7019"]],AUTHORITY["EPSG","6269"]],PRIMEM["Greenwich",0],UNIT["Degree",0.0174532925199433]],PROJECTION["Lambert_Conformal_Conic_2SP"],PARAMETER["latitude_of_origin",41],PARAMETER["central_meridian",-71.5],PARAMETER["standard_parallel_1",41.7166666666667],PARAMETER["standard_parallel_2",42.6833333333333],PARAMETER["false_easting",656166.666666667],PARAMETER["false_northing",2460625],UNIT["US survey foot",0.304800609601219,AUTHORITY["EPSG","9003"]],AXIS["Easting",EAST],AXIS["Northing",NORTH]]

Wifi CRS: EPSG:3857

Since they’re different, we need to use the to_crs method to make sure they’re all in the same coordinate system. We’ll use the EPSG:4326 coordinate system, which is one of the most common coordinate systems for geographical data. Then, we can overlay the two plots using matplotlib.

# If they're different, reproject the wifi data to match the census data

if census.crs != wfw.crs:

census = census.to_crs(wfw.crs)

# Create a new figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

# Plot the census data

census.plot(ax=ax, color='gray')

# Plot the wifi locations

wfw.plot(ax=ax, color='red', markersize=10, alpha=0.2)

plt.title("Boston Census Block Groups and Wifi Locations")

plt.show()

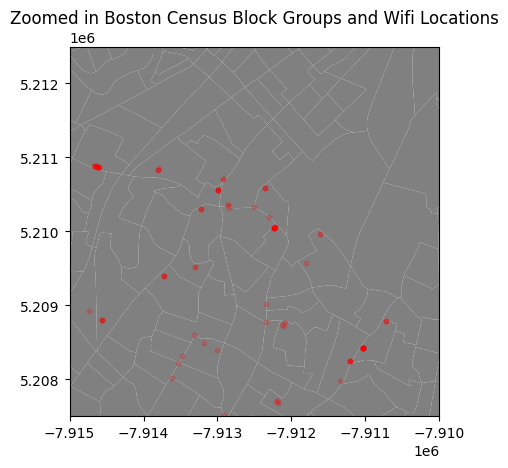

If you want to zoom in on a specific area of a map in GeoPandas, you need to add the lines: plt.xlim() and plt.ylim(). These functions take in the xmin and xmax, and ymin and ymax values of the area you want to zoom in on. You can find these values by looking at the x and y axes of the original plot.

# Same as before

if census.crs != wfw.crs:

census = census.to_crs(wfw.crs)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

census.plot(ax=ax, color='gray')

wfw.plot(ax=ax, color='red', markersize=10, alpha=0.2)

plt.title("Zoomed in Boston Census Block Groups and Wifi Locations")

# Set the x and y limits to zoom in on Boston

plt.xlim([-7.915e6, -7.91e6]) # xmin and xmax

plt.ylim([5.2075e6, 5.2125e6]) # ymin and ymax

plt.show()

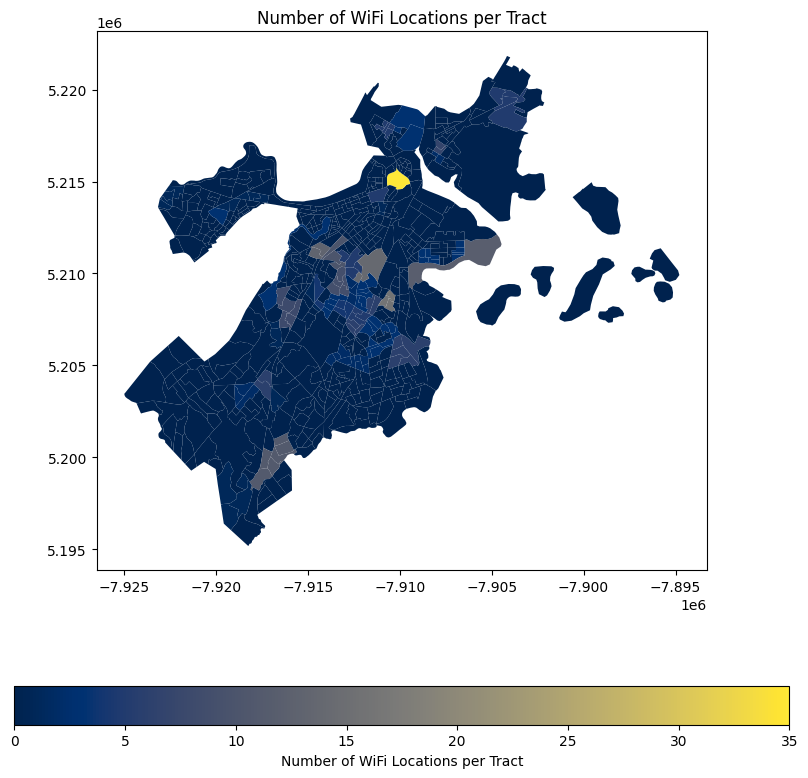

Make a Choropleth (color each census block according to the number of WiFi locations in it):

Now that both of our GeoDataFrames are on the same CRS, we can do a spatial join to find out how many WiFi locations are in each census tract. A spatial join is a type of join that merges two GeoDataFrames based on the spatial relationship between the geometries of the two GeoDataFrames. In this case, we want to know how many WiFi locations are in each census tract, so we will use the contains operation to find all of the WiFi locations that are within each census tract.

# Perform a spatial join between the census tracts and WiFi locations

wifi_per_tract = gpd.sjoin(census, wfw, predicate='contains').groupby('TRACTCE20').size()

wifi_per_tract.head()

TRACTCE20

000301 1

000603 3

000604 1

000805 1

030302 35

dtype: int64

The “contains” operation (as well as other spatial operations like “intersects”, “within”, etc.) uses geometric calculations based on the shapes’ coordinates (which have the same CRS) to determine spatial relationships.

For the “contains” operation specifically, it checks if all points of the other geometric object are within the current geometric object, and that their boundaries do not coincide.

For example:

from shapely.geometry import Point, Polygon

# Create a 5x5 square (tract)

polygon = Polygon([(0, 0), (5, 0), (5, 5), (0, 5)])

# Create two points (WiFi location)

point1 = Point(3, 3) # Inside the polygon

point2 = Point(6, 6) # Outside the polygon

# Check containment

print(polygon.contains(point1))

print(polygon.contains(point2))

True

False

We can now groupby the unique ‘TRACTCE20’ values and take .size() to get the number of wifi locations in each tract. Then, we can merge this with our census dataframe to get a new column with the number of wifi locations in each census tract.

# Add a new column to the census GeoDataFrame with the count of WiFi locations per tract

census = census.merge(wifi_per_tract.rename('wifi_count'), how='left', left_on='TRACTCE20', right_index=True)

# Replace NaN values (tracts without any WiFi location) with 0

census['wifi_count'].fillna(0, inplace=True)

# Now, create a new figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(10, 10))

# Plot the census data, color-coded by the number of WiFi locations

census.plot(column='wifi_count', ax=ax, legend=True, cmap='cividis',

legend_kwds={'label': "Number of WiFi Locations per Tract",

'orientation': "horizontal"})

plt.title("Number of WiFi Locations per Tract")

plt.show()

census[census['wifi_count'] == census['wifi_count'].max()]['wifi_count']

478 35.0

Name: wifi_count, dtype: float64

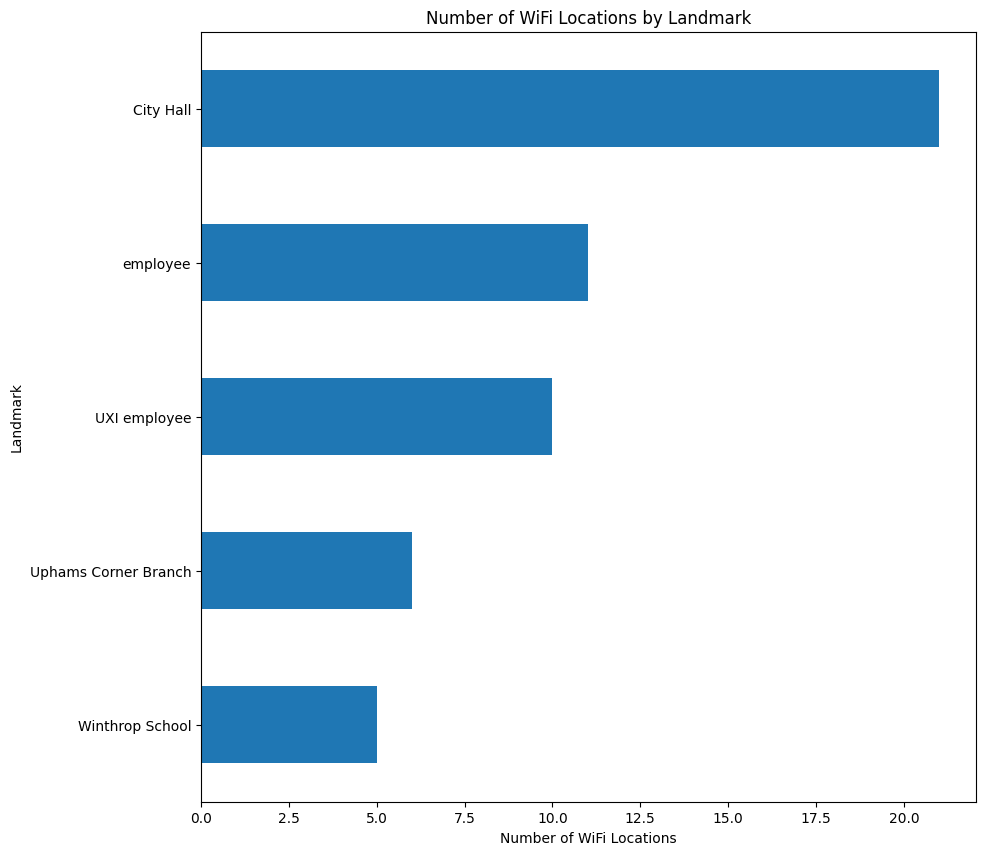

Looks like there’s 35 free wifi locations in this bright yellow tract, maybe the ‘landmarks’ column will tell us why…

wfw['landmark'].value_counts().head(5).sort_values().plot(kind='barh', figsize=(10, 10))

plt.title('Number of WiFi Locations by Landmark')

plt.xlabel('Number of WiFi Locations')

plt.ylabel('Landmark')

plt.show()

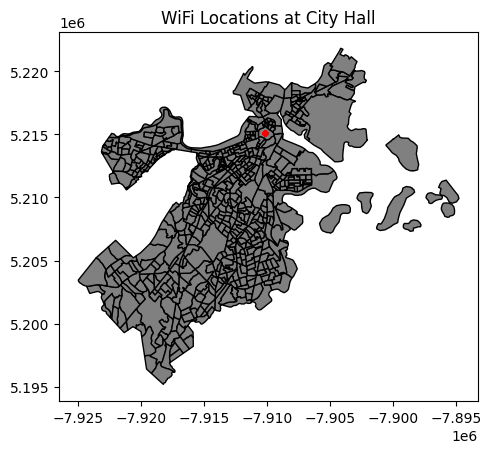

So it could be the City Hall, let’s graph it!

city_hall_wifi = wfw[wfw['landmark'] == 'City Hall']

if census.crs != city_hall_wifi.crs:

city_hall_wifi = city_hall_wifi.to_crs(census.crs)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

census.plot(ax=ax, color='grey', edgecolor='black')

city_hall_wifi.plot(ax=ax, color='red', markersize=10)

plt.title('WiFi Locations at City Hall')

plt.show()

Looks like we’re right! After plotting the subset of our dataframe where Landmark == “City Hall”, we can see that all of these points are clustered in that bright yellow census tract. Looking at the listed address of these WiFi locations, we can see that they are all located at 1 City Hall Square, which is the address of Boston City Hall.

Here are the unique device addresses of these city hall wifi locations:

city_hall_wifi['device_add'].unique()

array(['1 City Hall Square, Boston, MA 02201',

'1 City Hall Plaza, Pavilion\nBoston, MA 02201',

'One City Hall Sq, Pavilion Bldg\nBoston, MA 02201', nan,

'1 City Hall Plaza, \nBoston, MA 02201',

'One City Hall Sq, Pavilion Bld, IWF Room,\nBoston, MA 02201'],

dtype=object)

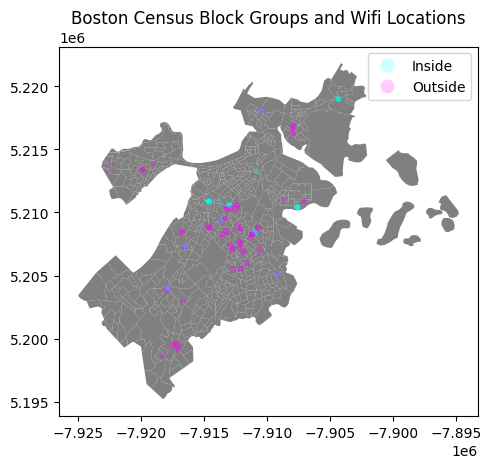

Inside vs Outside Wifi locations

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

census.plot(ax=ax, color='gray')

# Plot the wifi locations with color based on "inside_out" column

wfw.plot(ax=ax, column='inside_out', cmap='cool', markersize=10, legend=True, alpha=0.2)

plt.title("Boston Census Block Groups and Wifi Locations")

plt.show()

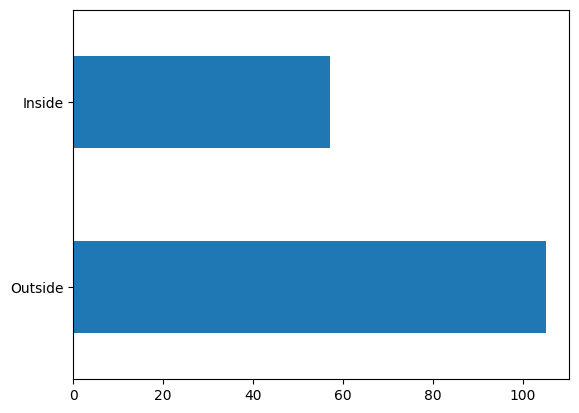

wfw['inside_out'].value_counts().plot(kind='barh')

plt.show()

Looks like most of our WiFi locations are outside. There’s probably a lot of “regular” EDA that can be done here, but since this is a GeoPandas/geographical analysis notebook, we’ll just leave it at that.

Closest Wifi location to BU

from geopy.distance import geodesic

# Coordinates of Boston University (accordign to Google)

BU_latitude = 42.3505

BU_longitude = -71.1054

# Create a copy of the WiFi locations and drop rows with missing coordinates

wfw = wfw.copy()

wfw.dropna(subset=['device_lat', 'device_lon'], inplace=True)

# Function to calculate distances to BU

def calculate_distance(row):

point = (row['device_lat'], row['device_lon'])

return geodesic(point, (BU_latitude, BU_longitude)).miles

wfw['distance_to_BU'] = wfw.apply(calculate_distance, axis=1)

# Find the WiFi location with the minimum distance

wfw[wfw['distance_to_BU'] == min(wfw['distance_to_BU'])]

| neighborho | neighbor_1 | device_ser | device_con | device_add | device_lat | device_lon | device_tag | etl_update | is_current | inside_out | landmark | ObjectId | geometry | distance_to_BU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | N_601230550253961587 | BCYF Tremont | Q2FD-4SE4-JW2S | BCYF-3rd FL GED | 1483 Tremont St, Boston, MA | 42.332317 | -71.09865 | BCYF Inside employee | 2023-06-12 | 1 | Inside | employee | 37 | POINT (-7914665.525 5210889.576) | 1.301774 |

In order to find the closest wifi location to BU, we need to find the distance between each wifi location and BU. We can do this using the geodesic function from geopy, which returns the distance between two longitudes/latitudes. Then, we can find the row where the distance is the smallest, which will be the closest wifi location to BU.

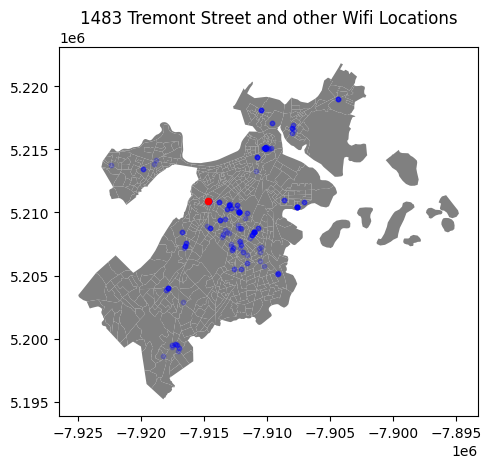

The closest wifi location to BU is the one at 1483 Tremont St, Boston, MA. It’s about 1.3 miles away from BU. Let’s plot it!

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

# Plot the census data

census.plot(ax=ax, color='gray')

# Plot the wifi locations

wfw.plot(ax=ax, color='blue', markersize=10, alpha=0.2)

# Plot the WiFi location closest to BU in red

wfw.query("device_ser == 'Q2FD-4SE4-JW2S'").plot(ax=ax, color='red', markersize=20)

plt.title("1483 Tremont Street and other Wifi Locations")

plt.show()

Wrap Up, Next Steps

There’s a lot more you can do with these datasets, for example, you could try finding the average distance between wifi locations, or incorporate another dataset with demographic information and try to find a relationship between income, education level, population density, etc and wifi locations. but this notebook should serve as a good starting point for your geographical analysis.

Click here to download this Jupyter Notebook and data (make sure you are signed in with your BU email)!